Family planning and emissions

Taking a left turn here this week to talk about family planning and emissions.

The reversal of Roe vs. Wade was a huge event for American politics and threw the abortion debate back into the spotlight. 27% of voters now say that their candidate must share their views on abortion, a record high, while 16% or voters say abortion is not a major issue, a record low.

For most people, the abortion rights issue is a deeply personal one. Abortion is seen as an infringement on a personal belief system, a symbol of the government’s protection of a personal human right, or a personal healthcare need (almost a quarter of women in the US will experience an abortion sometime in their life). It’s a sensitive and divisive subject, one that’s most often discussed as a social issue or, in some cases, a women’s issue.

It’s not just a social issue though. Family planning has documented effects on other parts of society, including workforce demographics, poverty, economic growth, childhood education, and public health. Its presence or absence can drastically influence how societies grow longer term, which can color how systems that work around that growth should be built. Climatetech, I suspect, is one of those systems. I’m writing on this topic today to better understand how to think about family planning relative to our climate problem.

Here's what I found:

- Family planning can reduce the climate burden, but estimates vary on its impact. According to Project Drawdown, family planning is the #2 (or #5 in scenario 2) most impactful source of emissions reduction, reducing an annual average of ~2.7 gigatons of CO2 equivalent over the next 30 years. This is consistent with common emissions / impact formulas like the IPAT framework and Kaya identity which identify population as one of their key variables.

I tried to back into those numbers to see what exactly within family planning was driving such a large impact.

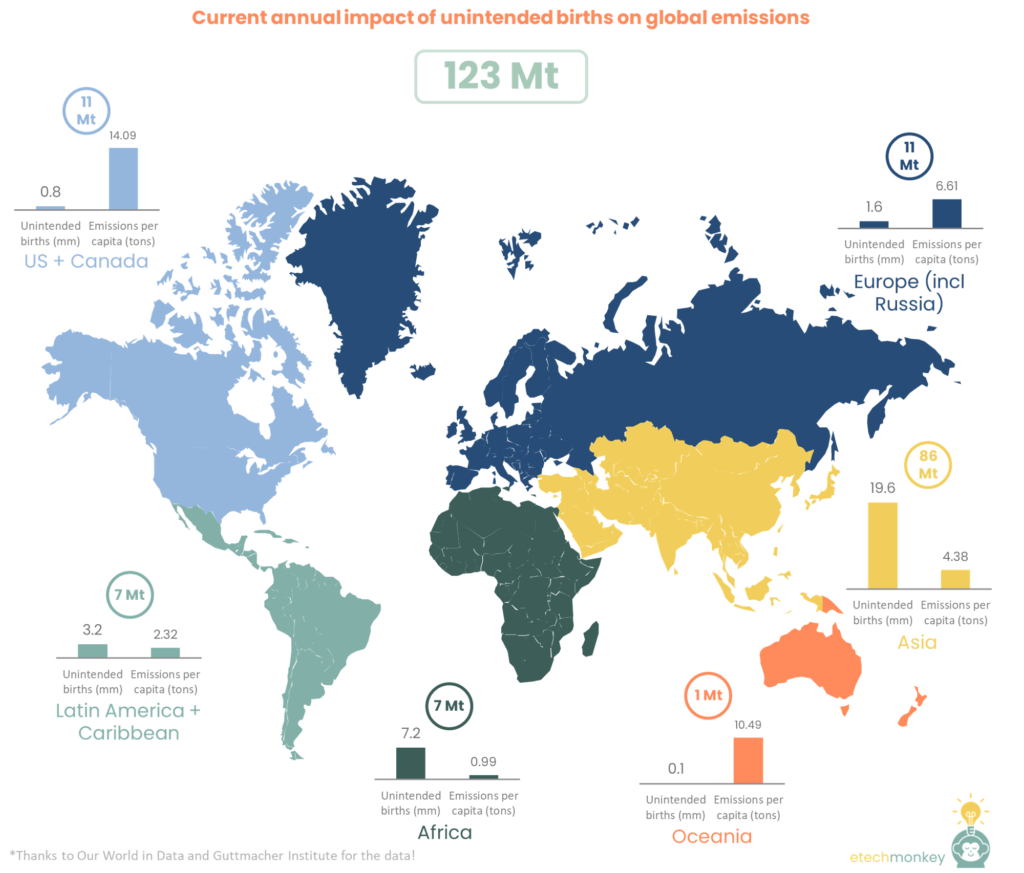

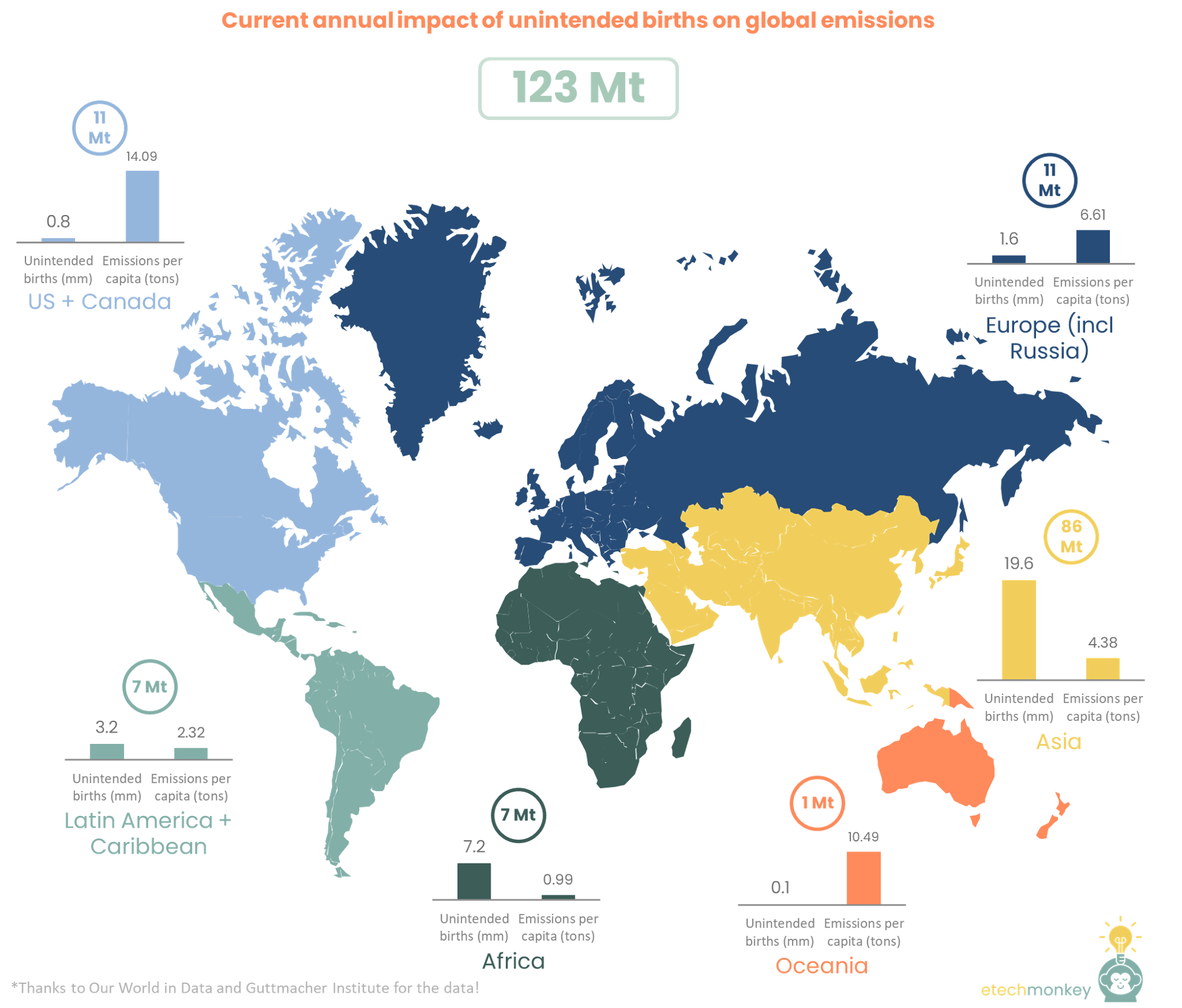

There are more than 120 million unintended pregnancies worldwide every year. Roughly 60% result in abortion, 27% result in live births, and the remaining 12% result in miscarriages / fetal losses. That’s nearly 32 million births that could have been avoided annually. The emissions impact of those 32 million people, when accounting for regional differences in per capita emissions and unintended births (unintended births tend to skew towards poorer regions with lower per capita emission and more births), is 123 Mt CO2e per year (weighted average emissions per capita of 3.7 tons), or ~0.3% of current world’s emissions. Adding in a 1.05% population growth, the annual emissions impact over the next 30 years of unintended births is ~144 Mt CO2e per year.

That still leaves 2.5 Gt CO2e unaccounted for in Project Drawdown’s estimates, and that’s assuming the impractical scenario that 100% of unintended births get avoided. I have to assume that the difference is due to unmodeled population decreases like above-average fertility rate declines due to systematic increases education and income level, something that isn’t captured in this data (the UN estimates that Project Drawdown uses as the basis for its “low” estimates has global population growing at an average of <0.5%, which is less than the US birth rate right now). Either way, 144 Mt is still quite a chunk of emissions. The entire ethanol industry emits only half that amount. - Family planning legislation in the US has a lesser but still meaningful impact on emissions. When looking at the US, the proportional impact of family planning is smaller due to an already below average rate of unintended births, offset slightly by the higher emissions per capita. A 700,000 reduction of unintended live births (again, assuming 100% of unintended births are avoided) results in 8-10 Mt of reduced CO2e (depending on if you use 15 tons CO2e/person, which is the median, or 12 tons CO2e/person, which is the carbon footprint of someone in the US living at the poverty line) and 9-11 Mt adding in population growth. That’s ~0.2% of US emissions annually.

I was curious to see how much of this number might we “unrealize” with the recent reversal of Roe vs. Wade. The implementation of Roe vs. Wade has been shown to decrease births by 4%, amounting to ~125,000 avoided births annually. Again, most of these avoided births are attributed to lower-income households. Applying the 12 ton estimate that we did above for someone living at the poverty line, that amounts to 1.5 Mt of additional emissions per year. 1.5 Mt is equivalent to ~0.02% of annual US emissions, which doesn’t seem like much on a relative basis but still is equivalent to the emissions from 300,000 cars per year. - These numbers still leave out some secondary effects of family planning, effects that can be positive or negative for emissions reduction efforts. Family planning does result in a noticeable increase in quality of life for the family unit. There is plenty of evidence that suggests that family planning helps women stay in school for longer and pursue more equitable employment, improving the socio-economic status of not only themselves but of their families and communities. Not only does this uplift allow developing societies the bandwidth to prioritize sustainability alongside basic human needs, it also helps people that are the most vulnerable to climate change impacts (i.e. low income communities) invest in adaptation and mitigation efforts.

On the other side of the equation is the increase emissions per capita that comes with quality of life. One case study of this is China. Though controversial, China’s 1979 one-child policy has been pointed to as one of the reasons for China’s accelerated economic progress. The rapid decline of fertility allowed more focused resource usage on the economically productive part of the population and also uplifted women’s education (though had other negative consequences on female births). Is it a coincidence that starting in 2001, 22 years after the one child policy was enacted (and when children born during the one-child policy started entering the workforce), China’s emissions per capita started rapidly accelerating, growing at an average rate of 10% between 2001 and 2011 vs. 2% in the previous decade? I’m not sure. China certainly did accelerate growth in that time through policy changes as well, but the demographic changes certainly didn’t hurt. By rough math, the avoided emissions from the one-child policy (400 million births x 2 tons/person/year = 800 Mt CO2e) was vastly trumped by the emissions per capita increases on the general population (1979 population of 986 million people x 5.8 tons/person/year increase in emissions = 5.8 Gt).

All this to say that family planning’s positive influence on growth and society is not negated by the potential environmental effects of a move up the prosperity index. It will be a necessary step for developing nations to take to achieve the ultimate goal of sustainable prosperity.

I think when I came into this topic, I had the notion (perhaps because I spent a lot of time with the Project Drawdown estimates from the last few weeks) that family planning would have a huge impact on emissions. But the reality is that while the numbers aren’t insignificant, they are modest compared to the potential impact of new technology solutions, especially ones that target our underlying industrial systems. We can use it as an effective solution, especially as it addresses other social and economic goals in parallel, but it definitely cannot be the focal point for an effective climate strategy.

Another point worth mentioning is that family planning has already come a long way, especially in developed nations where emissions per capita are highest. If we stop paying attention to family planning and let fertility rates run unchecked, there could be multiplicative effects on emissions far greater than that of developing nations. So it’s definitely something we need to make sure to maintain at sufficient levels to allow our emissions problem to not grow too large for us to handle (though many might say we’re already there).