GHG Emissions Ranking and Reporting: Step One is Admitting You Have a Problem

It’s actually fairly hard to track down public company GHG emissions data. The GHGRP (Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program) only releases data reported at the facility or regional level, not at the company level. Data at the company level is buried in individual, non-standardized 100-page long climate reports, often in varying flavors of charts, tables, and graphs. Scouring them all manually is a slog. Scraping them automatically is a college thesis-worthy data mining exercise.

Luckily, we do have the CDP, or the Carbon Disclosure Project. CDP’s database aggregates voluntarily disclosed emissions data from a questionnaire sent to thousands of companies. From that questionnaire, the CDP rate companies a score from A – F for their climate change transparency, performance, and leadership.

Of the ~180 companies A-scoring companies that made the list, 28 were financial institutions, 46 were consumer goods or retail trade companies, 37 were industrial services / industrial process / industrial manufacturing companies, and 30 were technology and telecom companies. Only 9 energy companies made the list – all utilities. No oil and gas companies.

The A-minus list does have a group of oil and gas players. Total, ENI, Repsol, Hess all made the CDP A-minus…and a larger handful more – Equinor, Suncor, Petrobras, Shell, ConocoPhillips – made the CDP B-list. Conspicuously absent from the list of “good” scores (defined as a B-minus or higher, which is generous by today’s high school standards) are the rest of the majors, most of the US independents, midstream companies, and oil service names. Out of the ~240 oil and gas companies scored in the database, ~160 have ended up with a big fat F. Most of these companies have ended up in this position due to lack of disclosure or response to CDP. Concho, for example, despite having a climate report, has an F in the system.

Is it fair to penalize companies that might have just accidentally thrown away their questionnaire in the mail? Or simply didn’t know what the CDP is?

As more and more of the energy industry’s future is tied to transition, the answer is increasingly yes. Just like how “good citizen” financial practice for publicly owned companies requires full transparency and adequate disclosure to investors, “good citizen” environmental practice for emitters calls for full transparency and adequate disclosure to the world. To do this in a meaningful way, participation in major disclosure initiatives like CDP is a requirement.

CDP tellingly describes its A-listers as “leaders” earning “leadership” points. As the CDP website states, “Our scoring measures the comprehensiveness of disclosure, awareness and management of environmental risks and best practices associated with environmental leadership, such as setting ambitious and meaningful targets.” CDP claims its high scorers are setting the gold standard for environmental leadership – which means that current environmental leadership is made up of largely non-energy companies.

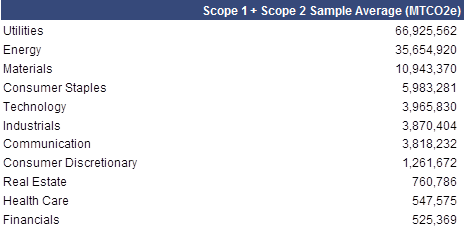

At the same time, a look at the average Scope 1 + 2 emissions numbers across sectors shows a reverse list (see Figure 1). Energy / utilities companies dominate in their high emissions numbers. An energy company averages emissions many times the emissions for a financial or technology company.

A high emissions number does not mean that the businesses are inherently bad. The energy industry is more prone to high emissions numbers than the technology or financial industries purely due to its proximity in the value chain to higher emitting industrial processes, but it makes up for that in its undeniably important role in human welfare. Reducing emissions while keeping up the responsibility of this role requires thoughtful environmental leadership from the players whose emissions matter the most. And that means full on participation in initiatives like the CDP.