How Bringing Data into Climate Tech Can Spur Exits & Catalyze New Investment Dollars for FOAK, Just As It Did in Biotech

Originally published on Medium

Part 5 of Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 (covered in the previous post on this blog), and Part 4

The TLDR:

Climate tech has an exit problem that looks like it might not get better

“Exits provide reference points for where startups are going and incentive for founders and investors to enter the space. Robust exit results are the missing puzzle piece in proving climate investing is not concessionary.” — that’s what CTVC wrote in its February 2023 analysis on climate tech exits. Exits are the ultimate source of liquidity for investors and without a robust set of exits, it remains challenging to present climate tech FOAK as a compelling investment opportunity for the purely financially-motivated investor.

Since CTVC wrote that piece, the exits problem hasn’t gotten better, with multiple articles lamenting the lack of exits this past year. (See Scarcity of exits at NYCW, Climate tech has an IPO problem, CTVC’s mid-2024 review highlighting lack of exits, Third Sphere’s NYCW “Climate Exits” deck, and PWC’s 2024 report pointing out the market contraction leading to fewer IPOs and exits)

And with the recent pullback in climate commitments and presumably the threatened reduction in corporate dollars allocated to investing in or acquiring new climate innovation, this exit problem is likely not going to get better without a huge ecosystem shift.

Here’s our argument: a concerted effort around FOAK DATA is the huge ecosystem shift we need to solve this exit problem. And biotech presents a template for this data-driven ecosystem shift.

Table of Contents

1) First, We’ll first dive into how biotech leveraged data to overcome its own exit problem and the specific playbook it followed.

2) Then, we’ll explore the central role data played in this transformation — how it derisked investments, created early validation mechanisms, and built transparency around milestones.

3) Finally, we’ll apply these lessons to climate tech, outlining concrete steps we can take to establish a data-driven validation framework, create an open-access project database, improve risk benchmarking, and give FOAK projects multiple shots on goal.

By the end, we hope to show that through shared data, there’s a better way to help FOAK projects be successful AND to prevent one project’s failure from dooming an entire technology vertical. A data revolution in climate tech is badly needed, but it isn’t just necessary — it’s entirely possible, and biotech’s history proves it.

PART I: Biotech’s history of bridging gaps

We’ve covered the data issue plaguing climate FOAK in detail (the what [Post 2, Post 4] and how [Post 3] and why [Post 1]) but we’ve mostly talked about this “data -> more FOAK” investment pathway hypothetically. The truth is that there is ALREADY an existing template for this pathway in US biotech (specifically in drug/therapy/anything that requires FDA clinical trials, but we’ll use the term “biotech” to refer to this subset).

Back in the late 90’s/early 2000s, biotech experienced a time that was very similar to climate tech today: declining corporate R&D budgets, lack of exits, and limited third party approval. And like climate tech companies, biotech companies faced a relatively unattractive investment profile for traditional VC: little to no early revenue, highly capital-intensive technology development that can have risks to human safety, and deeply technical IP. Value tended to hit an inflection point after Phase II trials, which is normally 8+ years after company inception, leading to a common valley of death, a timeline paralleled in much of climate tech.

How did biotech move on from this slump? As Baybridge writes, “[surviving] as an early-stage biotech VC in the 2000s was all about consistent singles and doubles.” In other words, increasing the probability of success and limiting dilution so you own more at exit and can exit modestly but at an acceptable multiple for the portfolio (sounds familiar…).

Faced with this challenge, the biotech ecosystem adapted and delivered. They hit their consistent singles and doubles, aiming at companies that were higher likelihood bets and that could exit earlier at reasonable value. Per Baybridge: “Many of these startups were not meant to become big, lasting companies, but were essentially vehicles for taking on a few key risks that pharma wasn’t comfortable with and then selling to big pharma once the major risks were taken out.”

We’ll dive into the playbook below but the sector recovered, growing over the next two decades (with a blip during the recession) and remaining one of the leading sectors for private capital deployed throughout that time.

PART II: Why data was central to this biotech revival

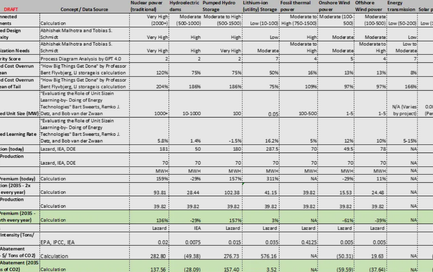

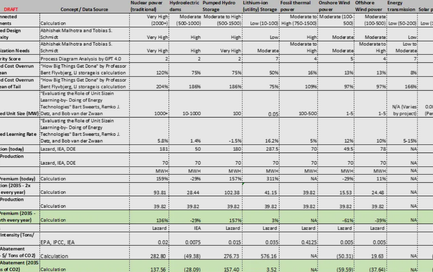

Baybridge lays out the playbook for hitting singles and doubles, summarized below:

- “Front-load key risks,” “In-house company creation: aligns company and investors around truth-seeking and killing things early,” “Assess robustness of science and test key hypotheses with seed funding before raising a big Series A,” “Start companies in house to control valuation” 🡪 Derisk as early and as cheaply as possible (cheap = less money & especially less dilutive capital)

- “Minimize translational risk: validated targets, well-understood biology, strong translational science, well-defined, homogenous patient populations,” “Extensive technical diligence, including in some cases independent reproduction of academic data” 🡪 Reduce scale up risk by having a well-defined scale up model with minimal unknown elements

- “Minimize commercial risk,” “Focus on severe unmet need and large potential clinical benefit,” “Fund capital-efficient development plans: orphan drugs, cancer with accelerated approval, indications with high unmet need,” “Asset-centric rather than platform companies,” “Reduce cost of clinical proof of concept: orphan drugs, severe unmet needs that allow flexible study design / accelerated approval, homogenous genetically defined patient populations, validated biomarker and other surrogate endpoints” 🡪 Choose a solution that has clear & specific commercial need, especially with a known cost-efficient pathway to development

- “Partner with potential buyers early on: ‘build to buy,’” “Non-dilutive corporate partnerships” 🡪 Build to be acquired & work with corporate partners while building to help minimize dilution and/or acquisition risk

- “Experienced managers to minimize operational risk and manage large, cross-disciplinary teams,” “Virtual companies with outsourced R&D” 🡪 Build with risk-minded team members that have industry experience, perhaps with the use of outsourced/fractional help to be cost efficient (side note: one can see a parallel between virtual biotech companies with outsourced R&D and climate tech DevCos building with “outsourced” climate tech TechCos)

Data is a common thread that runs through many of these recommendations. To derisk early & cheaply in the 2000s, many biotech companies turned to virtualization, the practice of reducing spend and building leanly by relying on outsourced labor and leveraging data & software to mimic costly labwork. To reduce scale up risk, biotech companies needed good scientific data, data on their patient populations, and data-driven technical models defining the “translation” from lab to clinical trial. To find capital efficient products with large market needs, biotech companies needed to have data on capital-efficient pathways to follow, market data on the problems with “high unmet need”, and data on the “surrogate endpoints” or early KPIs that indicate if a technology is scalable.

There’s also an interesting parallel we can draw between “virtual” biotech companies with outsourced R&D and distinct DevCo/TechCo entities in the climate ecosystem. While most TechCos in climate today are building their own DevCos, one can see an argument to separate the two, much as what has happened in solar, wind, and storage. We won’t go into this thesis in depth today but suffice to say that in order to build out an ecosystem in which DevCos can flourish separated from TechCos, there needs to be a good amount of data on the technology & scalability of the technologies or similar technologies developed by the TechCos available in order for a separated DevCo to take the leap of faith in licensing from a TechCo.

Another parallel we can draw is between targeting “genetically-defined, homogenous patient populations” and “controlling for uncertainty” in FOAK development. Using known patient populations allows a biotech company to better target & isolate positive outcomes. Similarly, FOAK development can control for uncertainty in using equipment that is most used in precedent, comparable infrastructure and designing as closely to comparable infrastructure as possible. That requires a good set of precedent data.

PART III: Climate tech’s next steps to building a similar data-driven “revival”

So what can we do to learn from biotech’s history in building out the future of climate tech FOAK?

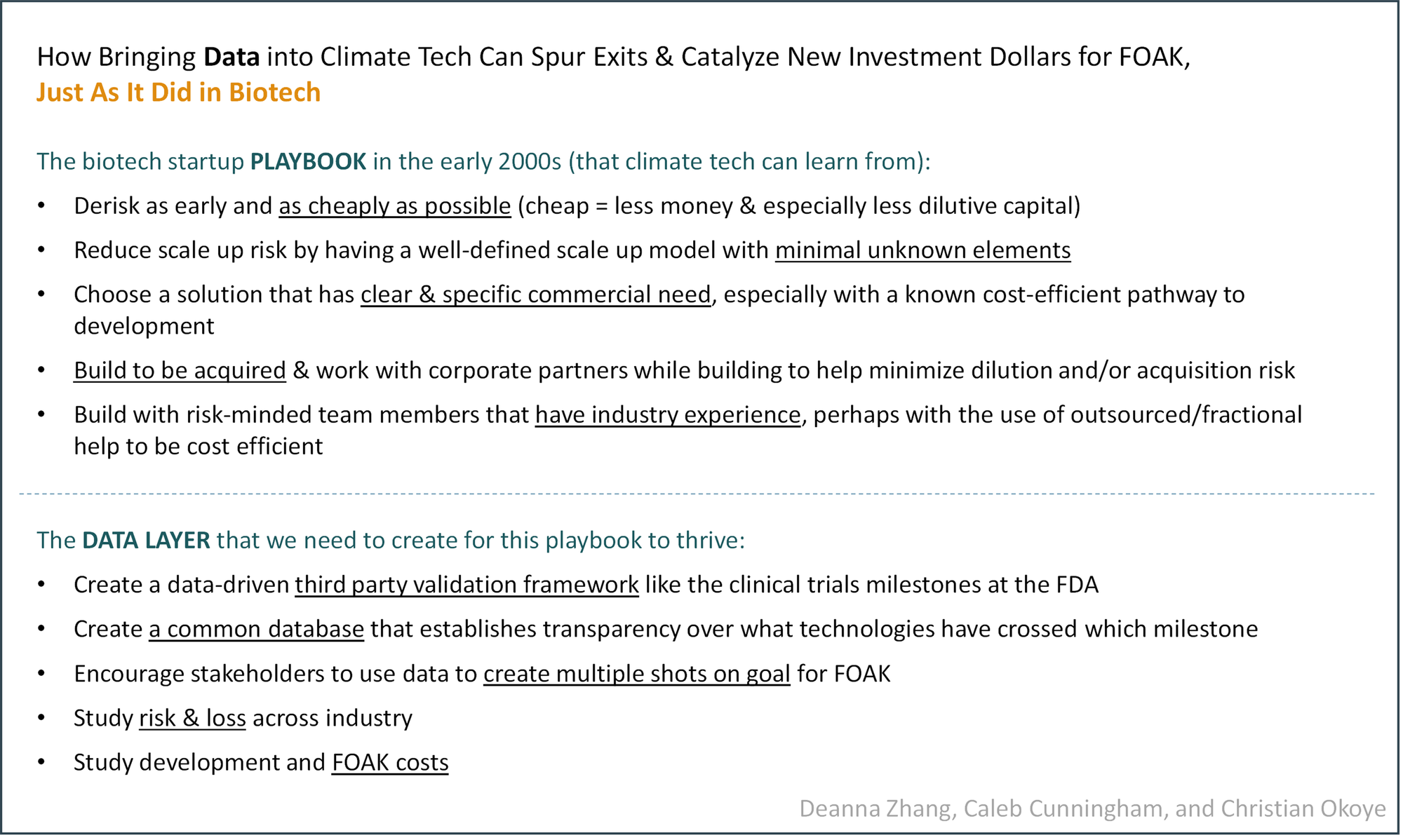

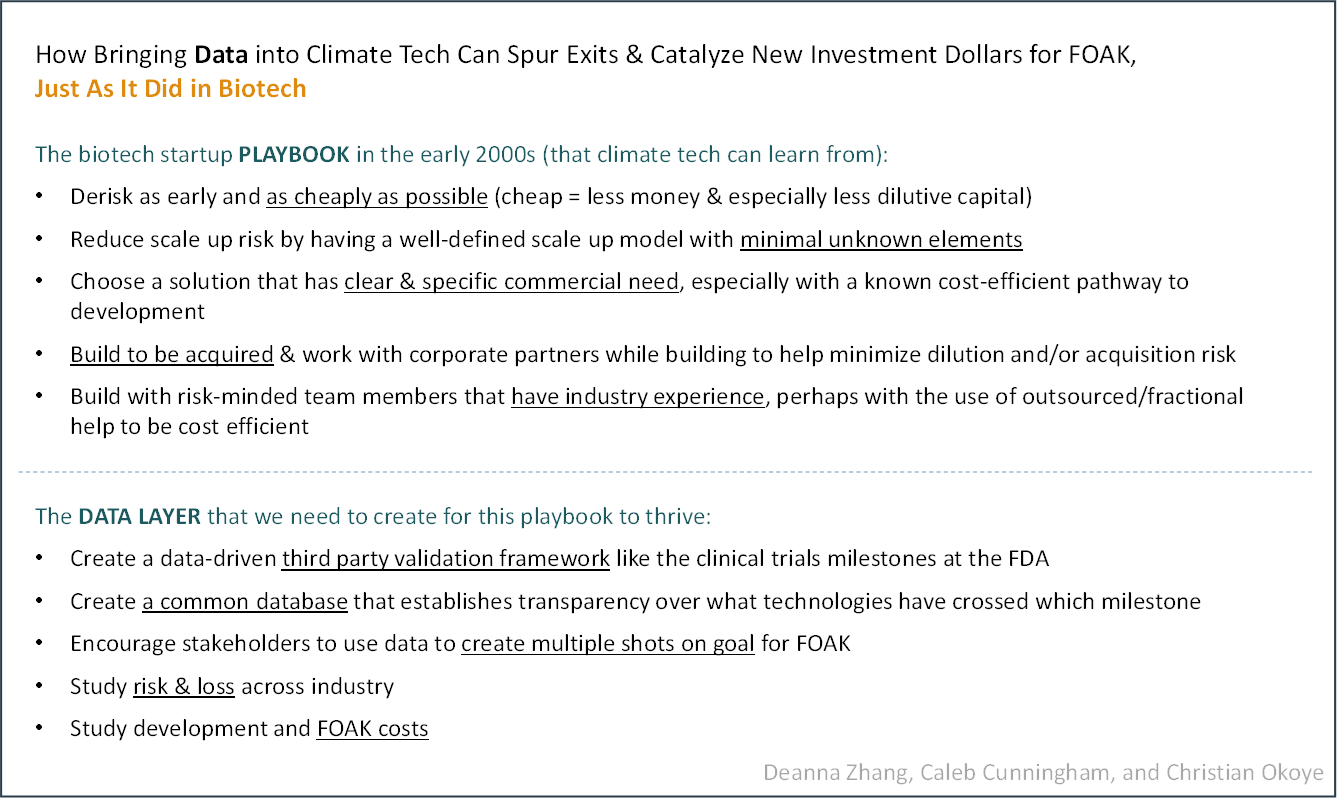

Climate tech startups CAN THRIVE with the biotech playbook outlined above. But they need the right data layer to do it. Here’s what we propose to create that data layer:

- Create a data-driven third party validation framework like the clinical trials milestones at the FDA: The FDA’s clinical trials milestones are the gold standard for defining risk in a drug or medical device development pathway. At each phase, there are clear elements of the technology that are being derisked, with each trial defining what the exact endpoints are that measure that derisking. The INDs, or applications for clinical trials, are reviewed by a central authority, the FDA, that gives some level of validation to whether the trials are adequately designed. Final approval of a drug requires extremely rigorous diligence by the FDA, with the application alone often involving over 100,000 pages. Thus, when a drug enters a specific phase, there’s a standard that’s kept in the design / data collected / analysis of the study in order to make sure everything complies with the standards set forth by a respected third party — one that importantly, sees applications across drugs/devices of all types regardless of financial benefit — to qualify that drug for commercialization. This serves well to clearly define a very complicated set of risks at that stage in a simple way, and to establish the value of a biotech startup. With this system, biotech startup value can be tied to the level of derisking in these trials, a normally very subjective measure — rather than the simple objective measures like revenue or customers acquired, by which “normal” startup stages are defined.

While there have been multiple frameworks to define climate tech milestones (which we discuss in Post 3: DOE’s TRL, ARL, MRL, and other RLs, Elemental’s CIP scale, our Project Readiness Level, Climate Brick’s “climate napkin”), there aren’t any central authorities to evaluate technologies/projects by these scales. The result is that everyone self-reports their measurements, often defaulting to a TRL description that is inadequate and taken with a grain of salt. In our minds, the next steps to establish a clear data-driven third party validation framework are to

1) reconcile these scales into one cohesive procedure for evaluating a new FOAK opportunity,

2) use precedent data to build both precision & objectivity into these measurement scales for each subsector (ideally we can get to a level of precision to where multiple evaluators using each subsector-specific procedure can get to the same score with little margin for error), and

3) establish some central authority (naturally, the DOE, but in the midst of the current upheaval, a fast-moving, not-for-profit research organization?) to evaluate technologies with these procedures.

- Create a common database that establishes transparency over what technologies have crossed which milestone: In biotech, ClinicalTrials.gov serves as a central database on nearly all current or future trials being conducted in the US. By law, clinical studies in the US, with few exceptions, have to submit to this database. The results of the studies are then required to be published at ClinicalTrials.gov within 1 year of the study being completed.

Not only does this open, central database provide a common repository by which anyone can review the results of a certain trial, creating the basis for scientific peers to easily review studies — it also enables investors and partners to conduct easier technical diligence on opportunities (scientific review, assessing the competitive landscape & benchmarking with other treatments/trials, validating phase initiation or completion and thus stage).

If we had something similar in climate — an open access database on all pilot, demonstration, and FOAK projects from companies that details methods, measures of success, data, and results — it could build the foundation for a data revolution in climate and completely upgrade the way we talk about and evaluate risk at different stages. One can see a world in which this database validates the uniqueness of a technology across all potential projects, establishes stages of a technology’s progress through pre-commercialization / early commercialization, and enables clear valuation uplifts (likely creating new opportunities for early exits) pre-revenue.

- Encourage stakeholders to use data to create multiple shots on goal for FOAK: Since risk is so clearly defined by the methodology & results of clinical trial data, whether a drug is commercialized is not solely dependent on the health of the company developing it. In other words, the success of a drug can be independent of the success of the company that currently owns it and can even be independent of the clinical trials it goes through. There are many examples of drugs that have failed under one company being sold then succeeding under another company and drugs that fail the first set of clinical trials succeeding in subsequent clinical trials. Publishing the methodology and data around a drug’s development helps separate out the merit of the technology from the merit of the development process surrounding it, something that allows drugs more than one shot at commercialization.

This is critically important to drug development, as it means a failure in process, management, sales, internal politics, funding, and the myriad of other developmental failures that could plague a drug does not shut the door permanently on a drug that could have a game changing effect on society.

As it stands in climate tech, a technology that stands up a FOAK project on its own only really has one chance to stand up a FOAK project. If it fails and the company shuts down, there is no clear pathway to 1) diagnosing the failure as one of the technology or otherwise (and usually it’s otherwise), and 2) either going back out to the market for the FOAK project with a fix to the failure or selling the technology to a second owner that can then stand up a second FOAK project with a fix to the failure. Most climate tech startups, unless they have enough capital to deploy multiple FOAK projects at once, only really have one shot on goal to get right the following: scaling the technology correctly, designing a safe & cost-efficient balance of plant, putting in the right team, signing on the right partners and offtakers and vendors on schedule, permitting and obtaining sites with enough lead time, submitting credits for approval, finding and structuring financing…. If any of these steps fail and lead the project to failure, and if the company doesn’t have additional capital or other projects in the pipeline, that’s it. The company shuts down and the technology gets shelved, reduced to being the object of someone’s “what I learned” backstory as they move onto their next venture. There is no second chance.

By building out a database that publishes the results of projects throughout the lifecycle of a technology, we can conceivably build that second chance. IP in one failure can get “revived” through M&A or additional funding to drive a second attempt at a FOAK project…and building out the secondary market for IP can even alleviate downside concerns for funders of the first FOAK project, lowering the cost of financing.

- Study risk & loss across industry: It’s well-known across the biotech industry that drug development does not have a high hit rate. MD Anderson estimates that it takes 24 targets to reach 1 drug approval, a rate of ~4%. The FDA publishes that ~7% of drugs from Phase I clinical trials get approved. And that success rate has been well-studied for many years now. This success rate is important because it grounds investors and partners and others that commit time and resources to a certain technology on the risk that they should tolerate and helps benchmark portfolio successes to an industry-wide success metric.

In contrast, climate tech success rates and FOAK success rates are unknowns because the data is unavailable and difficult to study. Because these success rates are unknown, investors and partners frequently expect hit rates that are much higher than reasonably achievable. This can lead to them not spreading their bets wide enough and portfolio-level underperformance. Long term, systematic underperformance hurts subsequent funds and capital availability. If we want to make sure we keep building up more investment (and that’s investment of financial and strategic resources) in climate, we need to study the success rates a little more closely, and that means we need the data TO study.

- Study development and FOAK costs: Like success rates, drug R&D costs are very well studied. Various estimates point to $1–2B in average R&D cost for a new drug, with that number ranging widely across therapeutic areas. R&D cost is also frequently tracked over time. Studying the cost to develop and commercialize a drug helps define budgets for individual trials and encourage the development of programs to lower costs.

We’ve covered extensively in past posts on why we need cost studies for specific technologies so we won’t belabor the point here. But suffice to say that biotech serves as a prime example for how cost estimates, enabled by the widespread availability of data, can be a powerful asset used by the community.

To be clear, we’re not saying that biotech and climate tech are exactly alike.

They are two different sectors with some markedly different characteristics.

For one, authority is naturally centralized in a regulatory body that can decide to go/no go a drug. To try and mimic this equivalent authority in climate is extremely challenging as the permitting bodies and third party technical validators will likely always be separate, and might unnecessarily introduce risk of political tampering.

Second, the human body is also a relatively “standard testbed” for drug development, making it much easier to define consistent measures of success / positive clinical outcomes in clinical trials. Contrast that with climate tech, where technologies are used and tested across a wide variety of environments with very wide definitions of successful outcomes. The lack of consistency in testing environments makes it hard to standardize diligence of projects in climate.

Third, the M&A value proposition for biotech is much more straightforward. Big Pharma needs to continue acquiring new drugs to backfill their pipelines and to capture market share before formulations become generic. It’s also more straightforward to integrate new drugs into a big pharma portfolio. In climate, on the other hand, the natural acquirers are much harder to identify since it varies across sectors, the case that growth via acquisition is necessary is much harder to make, and the integration of acquired technologies/platforms is much more bespoke given the breadth of industries under the “climate” umbrella.

Fourth, the company funding trajectory in biotech is much clearer. The biotech drug-development-company funding trajectory follows a classic silicon valley VC > Growth Equity > M&A exit to Big Pharma or IPO pathway. In climate, the pathway is less likely to deliver M&A exits and more likely to be VC > Growth Equity > PE > Infrastructure Funding or IPO. With the lower likelihood of M&A/near term exits delivering liquidity on VC 10+2 timelines comes a concomitant reduction in the incentive for new VCs to invest into the space.

But hopefully we’ve demonstrated that we can be inspired by our friends in biotech and that these key initiatives around data can make a huge impact on climate’s ecosystem health and exit potential.

By the way, it’s worth mentioning that we’re by far not the first to point out that climate tech can learn from biotech. Prime’s Karine Khatcherian includes it in their 2022 report on the FOAK problem and Michael Sasche and Jim Kapsis wrote about this topic in Latitude Media. We’re not talking crazy!

If you’re interested in collaborating on any of these initiatives and/or have data to contribute to this project, please reach out.

Thanks for reading,

Deanna, Caleb, and Christian