How Hardware Became a Four Letter Word in VC...and Why It Shouldn't Be: Pt 1

I often hear the words “Sorry, I can’t invest in hardware” Or “we’re only interested in capital light businesses” nearly everyday while speaking to others on our energy technology effort. It’s a very common wall to run up against.

Out of the collective $167B raised in the US in 2019 for venture capital deals, $94B or 56% went to software. Within the $73B raised for non-software startups, 82% went to healthcare, services, and consumer goods. Only the remainder - 18% of the non-software pool and 8% of the entire $167B - went to what can be categorized as “hard assets” – startups that specialize in commercial products, IT hardware, energy equipment, and industrial equipment.

For startups that need the most capital to scale, we’ve allocated the least.

It wasn’t always like this

Modern venture capital traces its roots back to the 1940s. As Nicolas Colin details in his essay on the history of venture capital, the emergence of these financial entities came as a result of a technological fervor that began in WWII. The US, fueled by wartime tensions (and those that continued through the Cold War), had a newfound desire to fund scientific and technological breakthroughs. Money poured into R&D efforts at academic institutions to develop technology that would benefit the US military. As a result, we can thank the 1940s - 60s for inventions like radar, the jet engine, rocketry, penicillin, microwave, and the atomic bomb.

But a problem emerged within this innovation renaissance. Commercializing these emerging technologies was a struggle. Underwriters and lenders were used to valuing businesses that were either regular way retail businesses with existing customer bases or businesses with tangible assets that could serve as collateral. Technology businesses fit in neither of these categories. As Colin puts it, “[Tech businesses] couldn’t borrow from banks because their business model was unknown and they still had everything to prove. And they couldn’t raise capital from the public because no financier could value them.” So who would fund these new businesses? This gap in the market quickly became a boon for investment firms started by wealthy families, who saw the opportunity and could afford to take the risk. These first mover investors enjoyed much success in what was a virtually untapped market.

The next boom of venture capital after that continued to fund hard asset technologies. Semiconductors, transistors, microprocessors…and of course, personal computers. Venture capital-funded innovation back then was linked to the production of devices and electronics. But that soon changed when writing software for those devices established itself as a separate industry.

A match made in heaven

Venture capitalists soon found themselves more and more interested in this subspace of ICT, and for good reason. Software was perfect for the venture capital model. Institutional venture capital firms have an investment horizon of 5-8 years, typically make small investments in a large number of firms, and require big returns on a small number of investments in order to make up for the higher startup failure rates. All of this combines to make fast-scaling, low capital cost investments the perfect target for venture capital.

Moreover, the mass proliferation of the venture capital model combined with the lengthening time to exit means that more and more of the future value of a startup becomes concentrated in the ability of that startup to raise subsequent private capital rounds. The modern venture capitalist has to weigh factors that have less to do with the underlying technology and more to do with how this company might be viewed by others. What is the risk that this company might not be able to raise more capital in the future? Would x firm down the street understand and believe in the technology enough to able to invest with me at a later date? Are others in investor space generally looking at this type of technology? How easily sellable is this technology to the investor community?

This line of thinking plays into why venture capitalists invest in “clubs,” like easily understood technology, and like staying within generally accepted areas of interest. This translates well to software. Software often has a straight forward value proposition, its proliferation is embraced by many investors regardless of technical background, and its history of fundraising success provides assurance that there will be a healthy number of investors that look at this type of technology. Software’s popularity in the VC community has in itself cemented its preferential status over other types of technologies.

An evolution waiting to happen?

Unfortunately, this line of thinking also plays into why it’s such an uphill battle to encourage more investment in hard asset technologies. Understanding the superiority of one technology over another in this space often requires scientific or technical knowledge, which presents a hurdle in limiting the number of investors that would have (or care to devote resources to) understanding the landscape. Differentiated hard asset technologies also tend to be nichier areas that aren’t widely marketed as “hot spots” for VCs. The perceived lack of club-worthiness, high capital intensity, and longer time to scale raises the perceived risk for an incoming investor and makes it difficult for him/her to value the business.

Which is precisely what makes them a gold mine. As we saw in the history of venture capital, the lack of ability by incumbent investors to value to certain types of businesses led to the emergence of a whole new class of investors for those businesses. These investors saw the opportunity and invented a new financial entity to handle a different risk profile.

The current venture capital model has evolved to invest in software and asset light businesses. But that’s no reason why investors should shun hard asset technologies. As we see everyday in etech, the number of hard asset technologies increase by the day as the world moves from consumer-led digitalization to industrial-led digitalization. These technologies will increasingly need capital to move innovation forward. And I believe they will find it in the venture capitalists that evolve their fund structures to accommodate them, much as they did once before in history.

Next time we’ll explore what that might look like…

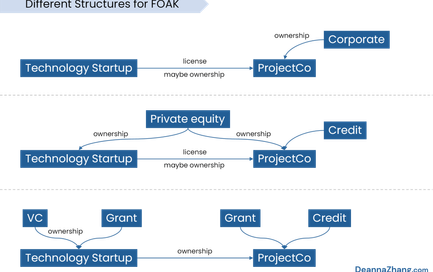

CERAWeek Reflections, FOAK Happy Hour Diagrams, and New Blog (no more Etechmonkey!)

Climate tech theme to watch: decentralization