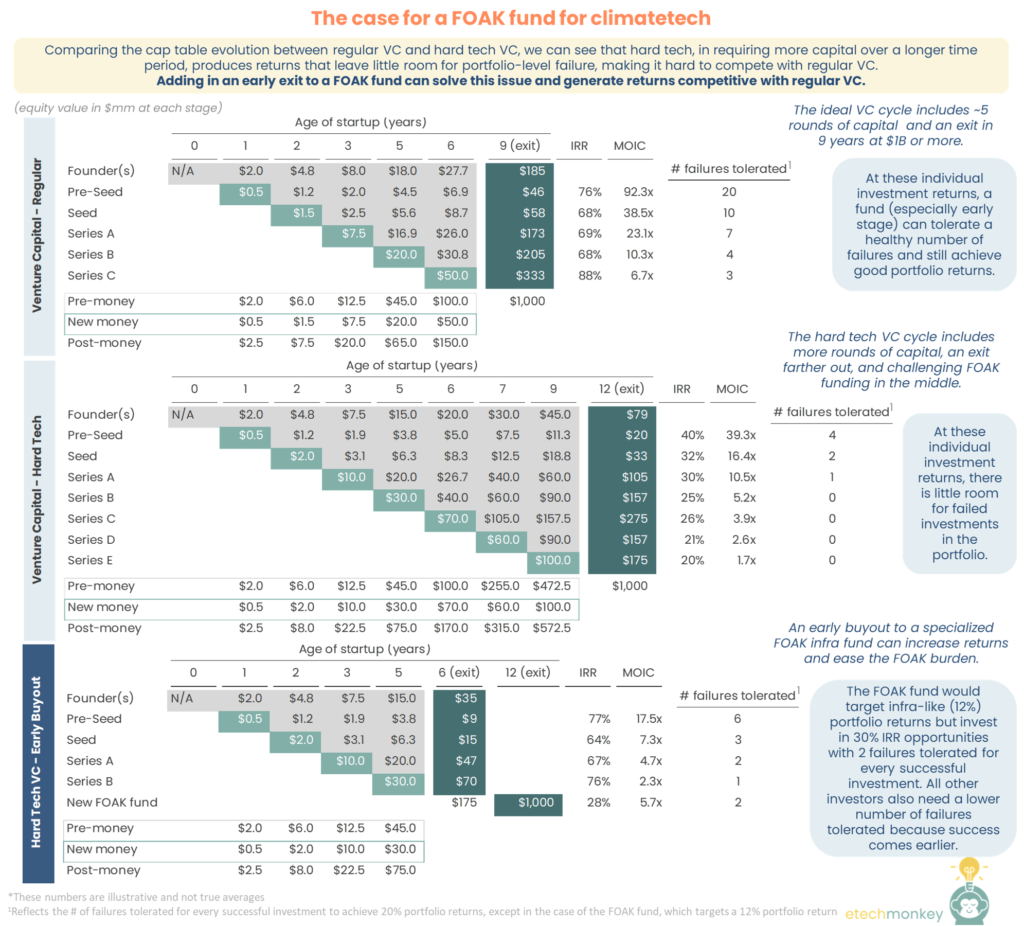

This week I had a grand plan to write about the economics of first commercial facility / FOAK commercial and why it makes complete sense to invest in these projects. But it was much more difficult to make the numbers work than anticipated. Even if a company gets over the FOAK hurdle, the lengthy time to exit coupled with the higher capital need results in returns for venture investors far from competitive to regular way venture investments.

There are paths to achieving competitive returns to regular VC – some existing ways include having philanthropic or government capital come in at FOAK stage, which can ‘lever’ up a project with non-dilutive financing, pursuing a licensing model, which, with the right partner, can allow a company to scale faster with less capital requirements, or recruiting an evergreen fund or fund-like operating entity that can provide flexible financing at multiple stages to accelerate the scale up.

But the path that is most murky (or at least was to me when I decided on this topic) is how to achieve competitive returns with a traditional institutional capital cycle.

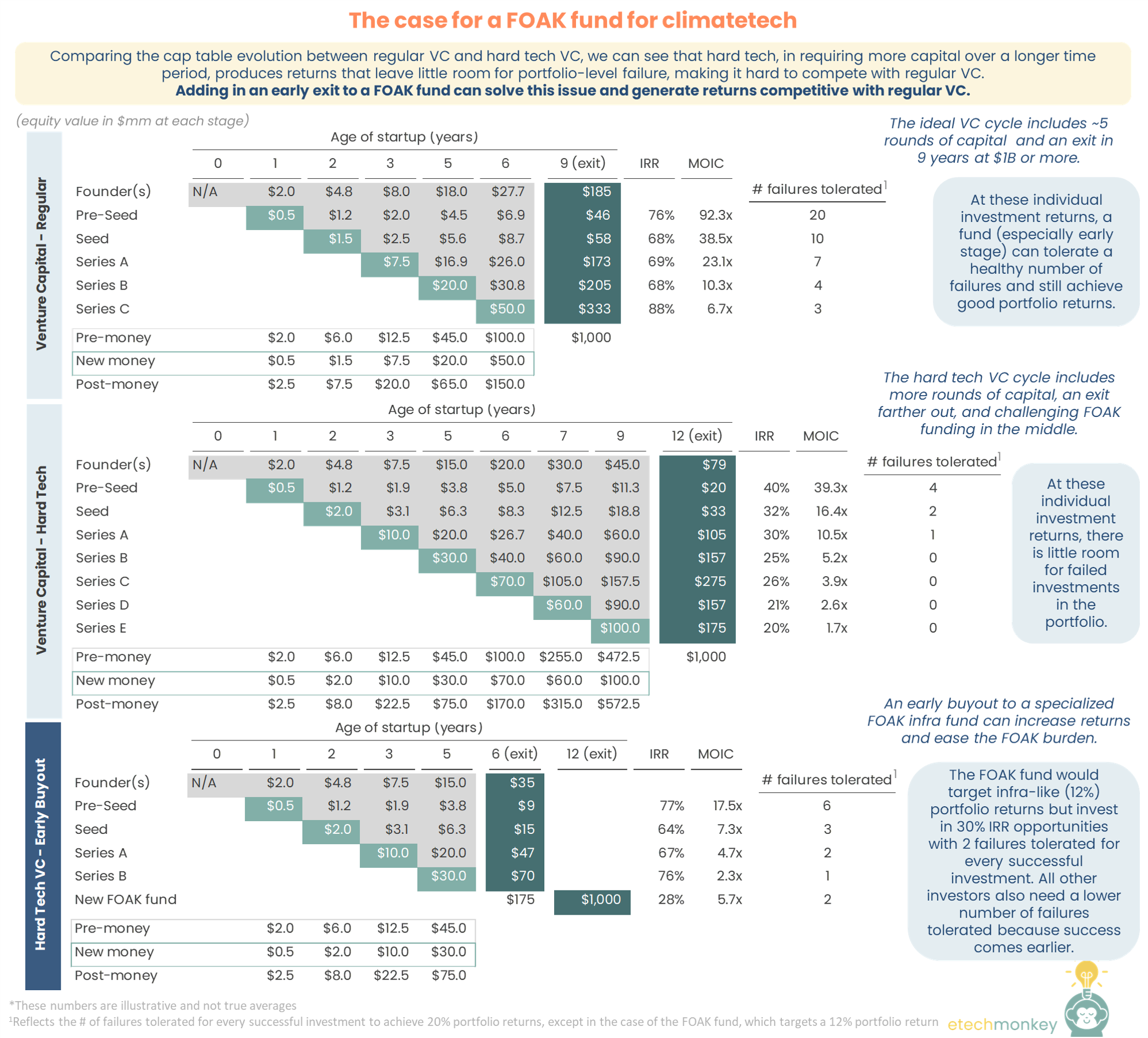

After experimenting with a rough model, I found that one way you can achieve competitive returns is by creating a FOAK-focused fund and encouraging companies to early exit to this fund. The early exit helps early stage venture investors find liquidity sooner, increasing IRRs and the likelihood of a successful investment. For the FOAK-focused fund, acquiring the company before FOAK means having the ability to capture all future facility economics vs. competing for 2nd facility and beyond economics with very low cost of capital. The likely levered returns past first facility substantially reward the FOAK investor for taking the FOAK risk.

This FOAK fund is not unlike a private equity firm that aims to acquire a company and lever it up before exiting in a few years. The difference is that this FOAK fund would aim for infra-like returns (10 - 15%, or the higher end of infra) at the portfolio level and private equity-like returns (20 - 30%) at the individual investment level, building in some expected failure rate (in the example below, 2 out of 3 investments can fail and the portfolio will be fine) similar to a venture fund to go from the individual investment to portfolio level returns.

The FOAK fund is a novel concept because 1) infra investors are generally extremely risk averse and don’t think about their portfolio in failure terms, 2) private equity investors do balance their portfolio according to expected return but also don’t necessarily build in a failure rate and don’t aim for as modest of a portfolio return, and 3) venture investors do think about failure rate but don’t typically look for opportunities to optimize for cash flow or lever up an investment. A vehicle that combines elements of private equity, infrastructure, and venture capital can address the imperfect match of each one of these traditional vehicles with the FOAK problem.

I don’t think there is something out there in the market today that looks like this…the closest is Generate Capital and their strategy of acquiring, operating, and scaling sustainable infrastructure companies. But I haven’t seen an institutional investor that addresses the FOAK problem. Perhaps someone can correct me here!

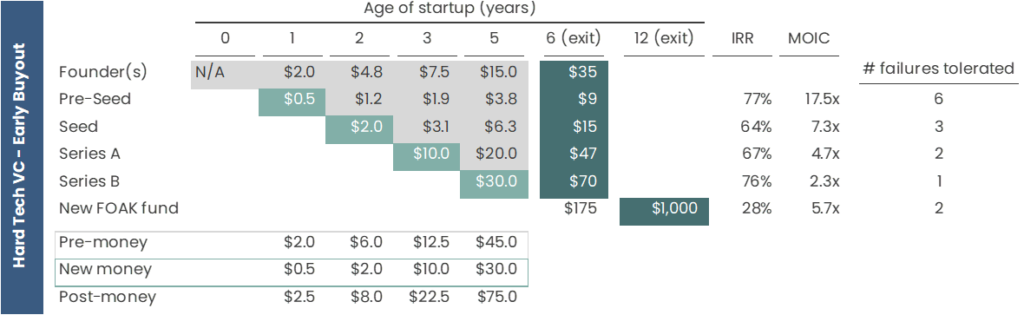

Here’s how the returns stack up in this illustrative example:

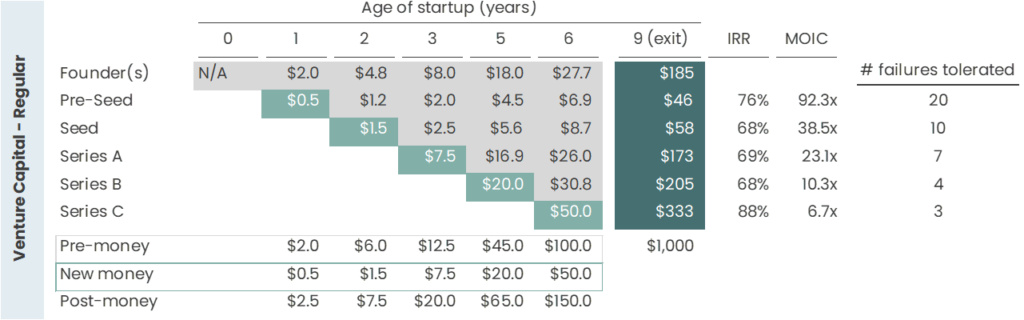

A typical venture cycle runs 4 - 5 rounds of funding before a company exit. Because of the high failure rate of startups, VC investors target a homerun exit – $1B or more in less than 10 years. Putting in some reasonable assumptions for round sizes and valuations up until that point, we get that, for this individual investment, a Pre-Seed investor can expect a return of 76% IRR / 92x MOIC, a Seed investor can expect a 68% IRR / 39x MOIC, a Series A investor can expect a 69% IRR / 23x MOIC, a Series B investor can expect a 68% IRR / 10x MOIC, and a Series C investor can expect an 88% IRR / 6.7x MOIC.

If we assume these returns for the successful homerun investment, that means that, in order to achieve a minimum of 20% portfolio IRRs, a Pre-Seed investor can have 20 failures to one successful investment, a Seed investor can have 10 failures, a Series A investor can have 7 failures, a Series B investor can have 4 failures, and finally a Series C investor has the least amount of wiggle room with 3 failures.

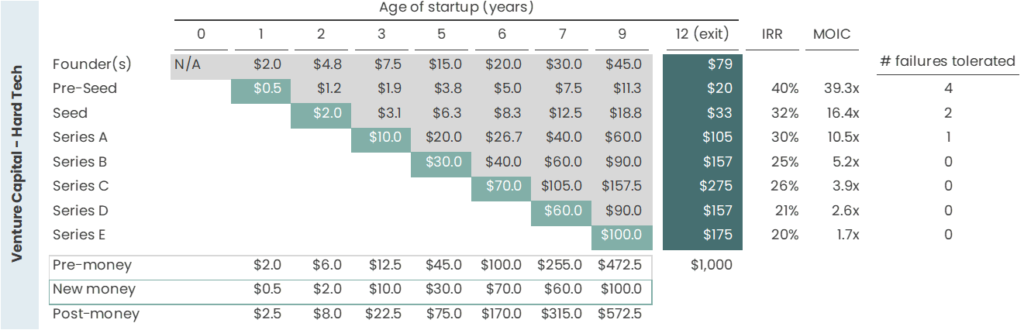

Moving on to the hard tech example, we assume that the round sizes increase due to greater capital intensity, two more rounds of capital are added to fund additional development, and exit gets prolonged 3 years until the 12th year of the startup’s existence. In this case, the returns are lowered to 40% / 39x for a Pre-Seed, 32% / 16x for seed, 30% / 10x for Series A, 25% / 5.2x for Series B, and 26% / 3.9x for Series C. Series D and E investors get a 20 – 21% or 1.7 – 2.6x return. The failure tolerances are significantly decreased, with Pre-Seed investors only allowed 4 failures to maintain a 20% portfolio return, Seed investors 2 failures, Series A investors 1 failure, and all other later stage investors no failures (i.e. every investment must be a success, a tall order for this type of risk capital).

Now we come onto the early exit case. In this scenario, the company raises a few rounds of capital to develop the technology to the point where it’s ready for FOAK commercial. Then, the company exits early to a FOAK fund. The FOAK fund acquires the company at a lower discount rate than what the VC investors would normally target, therefore being able to pay more than what a VC would have valued the company. After the FOAK fund acquires the company, it helps the company get past FOAK and move onto being a levered fully functioning infrastructure owner-operator, after which it can be exited.

Exiting early allows the Pre-Seed investors to realize a 77% / 18x return, the Seed investors a 64% / 7.3x return, the Series A investors a 67% / 4.7x return, and the Series B investors a 76% / 2.3x return. Though the MOIC is lower, the IRRs compare since the capital is returned a lot sooner. Exiting early also allows for a lower failure threshold, since the liquidity event for these investors is no longer dependent on getting past FOAK. Thus the 6 failures for Pre-Seed, 3 for Seed, 2 for Series A, and 1 for Series B, while lower than in traditional VC, reflect an easier success case.

For the FOAK fund investor that invested with a premium valuation to a VC, they would still be able to realize an exit at nearly 30% IRR and 5.7x MOIC, a very healthy return for any private equity or infrastructure investment. Because this investor is taking FOAK risk, there is a chance that the investment fails in a binary fashion (vs. half-failing or generating a partial return), similar to a VC investment. In this case, with a 28% individual investment return, the FOAK fund investor can tolerate a reasonable 2 failures for every success case to achieve a “risky infra” return of 12%.

TLDR;

Investors, new or existing in climatetech, can create a functioning FOAK strategy that can make investing in FOAK a financially attractive proposition.

Founders in hard tech climatetech can look to early exits as a means of scaling and providing liquidity to early investors. Also early exits to risk-taking infra investors can be more lucrative than continuing with the venture cycle.

Service providers can consider encouraging and supporting the creation of these FOAK funds.

IRA: Timing is everything

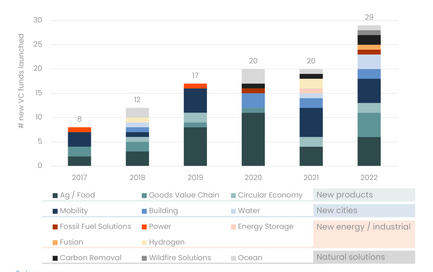

The emergence of specialist climate VCs