There’s been a LOT of money poured into climatetech over the last few years and even with the recent downturn, new money keeps coming in. According to CTVC, 2022 has seen an uptick in the number of new climatetech VC investors announced (45 -> 47), despite rising interest rates and a broader market slowdown for VC. It seems that the LPs of the world – endowments, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, mega-family offices – are still quite bullish on climate and hungry for new early stage funds in this space. And as climatetech deal activity (as measured by deal count) also hasn’t slowed, new fund managers continue to have opportunities to deploy capital in.

So the environment for being an investor in climatetech seems to be as good as ever these days…but has it evolved at all in other ways? That’s the question I was asking myself after I read this update. I suspected that the VCs that are raising money today in climatetech are of a slightly different flavor than the VCs raising money in climatetech a few years ago.

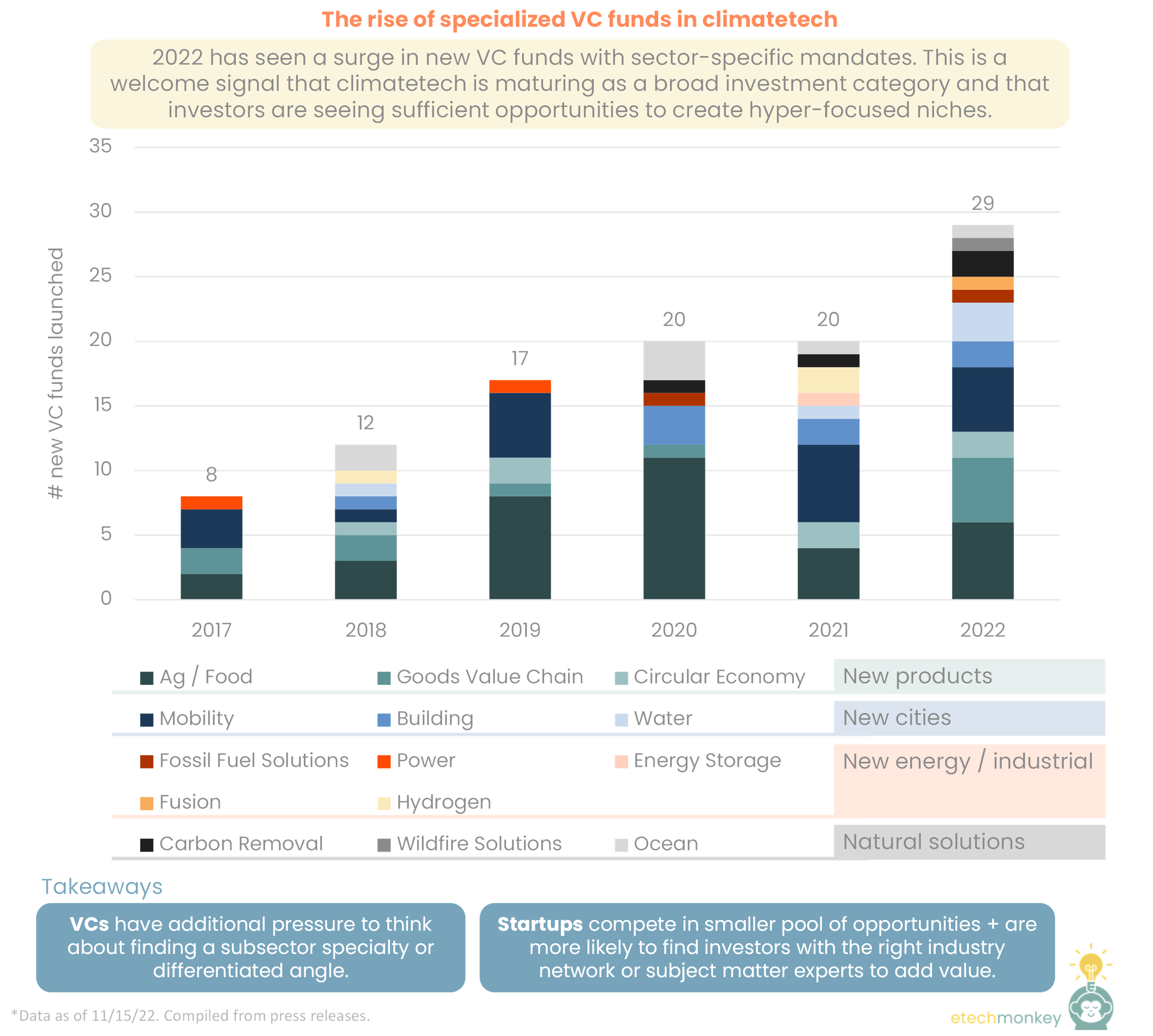

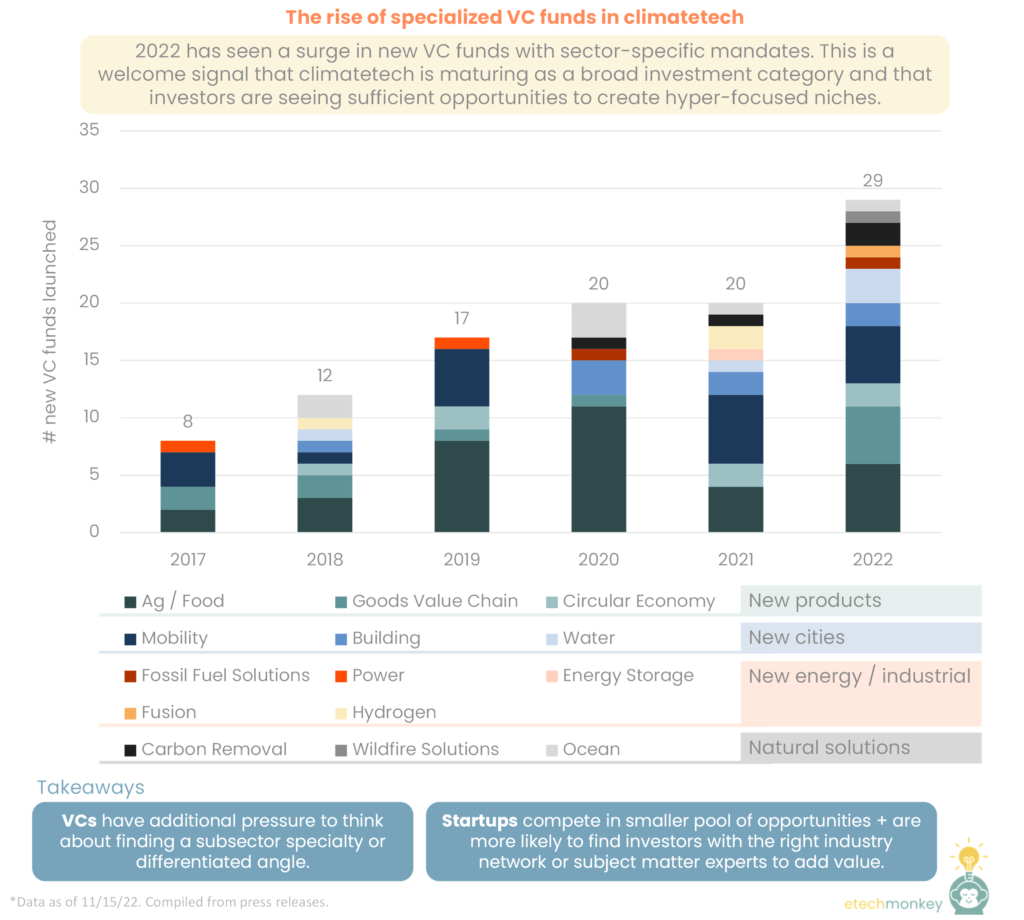

Examining the climatetech-oriented or related funds that have been raised over the last 6 years, I found that there’s been an interesting evolution that’s been happening when it comes to sector specialization. While most of the funds raised in the early days of climatetech / cleantech were generalist in nature, recent funds seem to have erred to choosing specific niches within climatetech like alternative proteins, buildings, or circular economy.

A taste of some of the announcements this year:

- Lowercarbon Capital’s $250mm fusion fund and $350mm carbon removal fund

- Propeller’s $100mm fund for ocean-related climate technologies

- Energy Capital Ventures’ $61mm fund for greening the natural gas industry

- Emerald’s $217mm sustainable packaging fund

- Convective Capital’s $35mm fund for wildfire solutions

- Capricorn’s $26mm industrial biotech for cleantech fund

- Burnt Island Ventures’ $30mm water fund

A total of 29 specialist climate funds have been launched this year, up 45% from last year. That’s out of a total of 106 specialist climate funds that are actively investing. These 106 funds span 14 specialties which can be aggregated into 4 main categories. All of this is shown in the chart below.

Some observations:

- Early specialist funds were concentrated on new ag/food and mobility. In the last two years, specialist funds cover a more diverse set of specialties.

- These funds don’t necessarily have to be completely new funds. 11% of these new specialist funds come from existing VCs with a more generalist or broader focus.

- This dataset only shows institutional specialist funds. Other specialist funds naturally exist through corporate venture capital, where strategics typically aim to invest in specialties that can complement or overlap with their existing business. Having more institutional specialist funds blurs the line a bit between the value add from a CVC and the value add from a VC, creating competitive pressure for the CVCs to add outsized strategic value or offer better terms in a transaction.

Overall, specialization is a positive development for the climatetech world. It’s at the very least a signal that climatetech is maturing as an investment category and fund managers are getting more sophisticated. It’s also a good sign that investors are seeing ample opportunities in climatetech for the long term.

The consequences of specialization are net positive. Having more specialized VCs places additional pressure on other VCs to think about finding a differentiated angle to offer to startups. This can push the investor world to developing better, more value-added relationships with their investments. For startups, having more options from specialist VCs increases competition in their favor, while taking money from specialist VCs can offer more strategic channels to the right industry network.

The other side of specialization is that specialist funds have limited options when it comes to pivoting in a challenging macro environment, leaving them vulnerable to industry-level macro shifts. Choosing to specialize is taking a risk that your chosen specialty will be around for years to come. Having an increasing proportion of specialist VCs in the climatetech ecosystem means that the overall capital stack for climatetech has more points of vulnerability.

But all in all, there are benefits of specialization to both the investors and startups.

For investors, specializing allows for:

- Easier deal screening. Less deals need to be vetted in a smaller market, allowing for more time to be spent with fewer companies. Having a public sector-specific mandate also means startups working in that area are more likely to know about you and proactively reach out.

- More thoughtful deal screening. Certain sectors may have sector-specific metrics that may be more relevant than traditional VC metrics like revenue or EBITDA. Things like quality of patents, technical benchmarks, partnership agreements, customer indications, etc. can be assessed in more depth in deal screening. For many VCs, especially ones coming in from tech to climatetech, using criteria that is too generalist may exclude startups that are expressing momentum in other ways.

- More leverage in attracting “hot” startups. In competitive, oversubscribed rounds, investors with clear differentiation and strategic value often have more appeal to startups than other investors, even those with more favorable valuation/terms. Similarly, a niche focus can help investors without a substantial track record argue their value to startups.

- Portfolio synergies. Investors that specialize are better able to aggregate resources particular to that specialty, like technical help, advisors, corporate partners, customer relationships, etc., for the broader portfolio, allowing startups in that portfolio to access those resources at lower cost. A specialized portfolio that brings together companies working around the same sector can also potentially find ways for companies in the portfolio to work together, officially or unofficially.

For startups, specialist funds can allow for:

- Easier investor screening. Most capital raises involve conversations with a hundred or so investors, with half of those being immediate dead ends because of lack of transparency by the investor on what problem areas they are interested in. Specialist VCs are very clear on this aspect, allowing startups to schedule those conversations without fear that time will be significantly wasted.

- Reduced competition with deals in other industries. Pitching to a generalist fund or a fund with a broad climate mandate can mean that your startup is being compared to other startups that have a totally different growth model. Investing in a materials science company selling into the auto market is worlds apart from investing in a carbon credit software company selling to consumers. Evaluating these deals together often time favors a certain industry or growth model instead of favoring the better company.

- More value-added partnerships. Specialist VCs often have more relationships within industry, which means that startups that partner with specialist VCs can access more relevant resources that can help them scale. Specialist VCs are likely also better able to contribute meaningfully to accelerating the startup’s growth as board members or advisors, making them better partners in the long run.

- Easier access to subject matter experts. Specialist VCs attract other specialist service providers and specialist partners, which means taking on a specialist VC can naturally allow a startup access to a wide array of subject matter experts in their sector. This can make the build process on a niche problem a lot less painful.

TLDR; we’re seeing more specialist VCs in climatetech. And that’s a good thing for the ecosystem.

CERAWeek Reflections, FOAK Happy Hour Diagrams, and New Blog (no more Etechmonkey!)

Climate tech theme to watch: decentralization